Discernment is the practice of distinguishing the voice of God from among the many different voices that vie for our attention, such as the expectations of others, cultural pressures, or even our own inner critic. The root word for “discern” means to “cut away.” So, discernment is the art of sorting through all these voices and our own tangled motivations and cutting away all but those that are of God.

Rev. Nadia Bolz-Weber wrote a heartfelt essay about our urgent need for prayerful discernment in this moment of our collective lives. With all that confronts us today—political division, familial strife, climate change, war, hunger, systemic inequalities, and global suffering—we might be tempted to throw our hands up in despair and abandon our efforts to make a difference.

Instead, she suggests we spend time with three guiding questions:

- What’s MINE to do, and what’s NOT mine to do?

- What’s MINE to say, and what’s NOT mine to say?And perhaps the hardest question:

- What’s MINE to care about, and what’s NOT mine to care about?

To be clear—this isn’t to suggest these important issues don’t deserve care from someone. Rather, we as individuals aren’t designed with the capacity to meet every need that comes to our awareness.

Consider this curious little story from spiritual writer Max Lucado…

A lighthouse keeper who worked on a rocky stretch of coastline received oil once a month to keep his light burning bright. Not being far from the village, he had frequent guests. One night a woman needed oil to keep her family warm. Another night a father needed oil for his lamp. Then another needed oil to lubricate a wheel. All the requests seemed legitimate, so the lighthouse keeper tried to meet them all. Toward the end of the month, however, he ran out of oil and his lighthouse went dark, causing several ships to crash on the coastline.

This story, like Jesus’s parable in Matthew 25:1-13 about the ten young women waiting for the bridegroom, presents an intriguing metaphor. What does the oil represent? Perhaps it symbolizes the good “fuel” that comes from exercise, artistic expression, or quiet time spent in prayer and gratitude—things we simply cannot give or do for another. It invites us to consider how are we called to let our light shine and how can we help others to light their own lamps so that they may shine too?

Maybe the thoughtful distribution of the oil represents good discernment, about understanding our calling—what we need to do and not do, say and not say, care for and let go. It might echo the humility of John the Baptist, who knew precisely who he was and wasn’t. While reminding us we’re not God, it affirms that our truest identity lies in our belovedness and belonging to God, allowing our false notions of self—both inflated and deflated—to fall away.

Perhaps these stories help us realize that alone, we are not the Messiah, but that our oil represents our specific, perhaps humble, yet essential contribution to the Body of Christ. We are a small, brief part of a very big, long story, providing a modest but mighty service to a greater mission of love and transformation.

Many of us struggle to envision and function as a collective right now. We feel alone in the wilderness, deeply concerned for our children’s and grandchildren’s future. Yet hope emerges in Jesus’s parables of seeds and in the image of the mature dandelion. The strong winds of change and uncertainty scatter our dandelion seeds far and wide. We exist in this liminal, sometimes uncomfortable space, not where we’re going and not where we’ve been.

Enduring patience is only possible when we recognize that what we await has already begun—growing from the ground beneath our feet. Joyful waiting means staying fully present to the moment, believing something beautiful and beyond our imagining has already started, trusting that God works even when appearances suggest otherwise. As Anne Lamott says, “Hope is revolutionary patience.”

May we take hope in the idea that sometimes the darkness doesn’t mean we are buried but that we have been planted.

Above all, trust in the slow work of God.

We are quite naturally impatient in everything to reach the end without delay.

We should like to skip the intermediate stages.

We are impatient of being on the way to something unknown, something new.

And yet it is the law of all progress

that it is made by passing through some stages of instability—

and that it may take a very long time.

And so I think it is with you;

your ideas mature gradually—let them grow,

let them shape themselves, without undue haste.

Don’t try to force them on,

as though you could be today what time

(that is to say, grace and circumstances acting on your own good will)

will make of you tomorrow.

Only God could say what this new spirit

gradually forming within you will be.

Give Our Lord the benefit of believing

that his hand is leading you,

and accept the anxiety of feeling yourself

in suspense and incomplete.

—Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, SJ

Discussion Questions

1. This piece defines discernment as “cutting away” all voices except those that are of God. In our modern world filled with social media, peer pressure, and constant information, what “voices” do you find most challenging to sort through when making important decisions?

2. The lighthouse keeper story presents a dilemma between helping others and maintaining one’s primary responsibility. Can you think of a situation where being “too helpful” might actually cause more harm than good? How do you balance helping others with maintaining your own boundaries?

3. The text compares our current situation to scattered dandelion seeds in “liminal space” – neither where we’re going nor where we’ve been. How does this metaphor resonate with your own experiences of transition or uncertainty?

4. The text suggests that we are “not designed to meet every need that is brought to our awareness.” How do you decide which causes or issues to focus your energy on? How do you deal with the feeling that you should be doing more?

5. Discuss how you understand the difference between being “buried” and being “planted” in times of darkness. What do you think distinguishes these two states? How might this perspective change how we view difficult periods in our lives?

6. The closing poem about trusting in “the slow work of God” and accepting feelings of being “in suspense and incomplete.” How does this message compare to society’s emphasis on quick results and having everything figured out? How do you handle the tension between these perspectives?

7. What role does our CCGP community play in maintaining your sense of purpose or identity? What other communities do you feel a part of? How have you adapted when separated from your usual support systems?

8. The passage includes the line “Hope is revolutionary patience.” What do you think this means? How might patience be considered revolutionary in today’s fast-paced world?

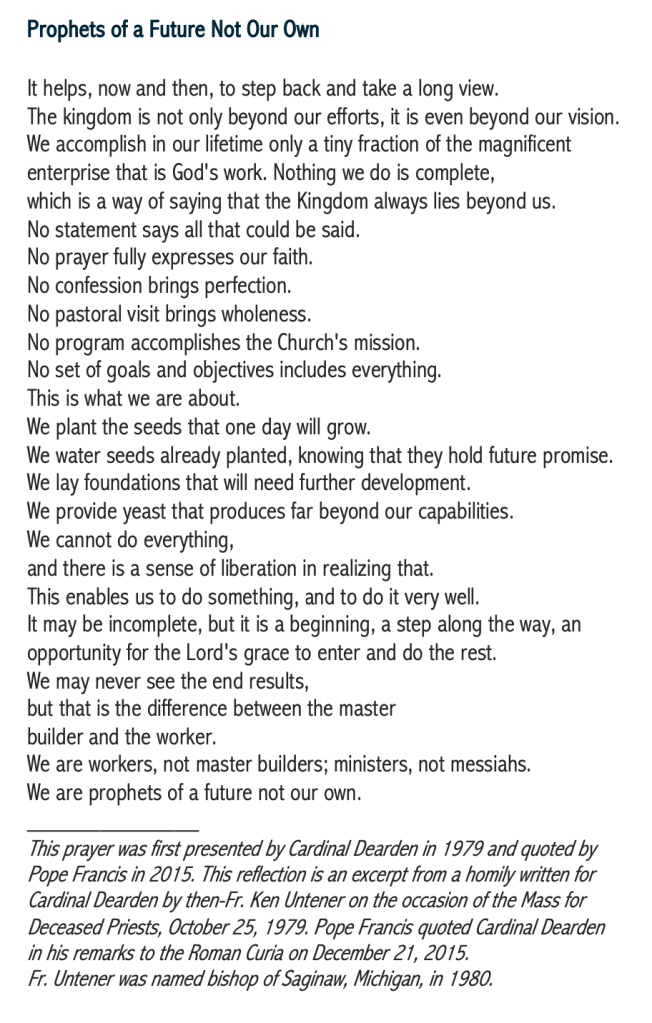

9. The piece entitled “Prophets of a Future Not Our Own” suggests that we are “workers, not master builders, ministers, not messiahs.” How might accepting this limited role actually be liberating? What pressures might it relieve?

Leave a comment